FCC Broadband Deployment and Oregon Policy

Posted on June 4, 2019 by Samuel Pastrick

Tags, Telecommunications

The Federal Communications Commission released its 2019 Broadband Deployment Report on May 29. For advocates, particularly those like CUB working to address digital inequality through new state and local policy, these annual reports induce a degree of eye rolling. They paint a less than accurate picture of the digital divide by acknowledging only advertised “access” and “availability” of broadband (25 megabits/second download over 3 megabits/second upload) service as opposed to actual usage, which is tracked by the American Community Survey (ACS). This dynamic undermines policy development and implementation at federal, state, and local levels.

The FCC’s Broadband Deployment report stems from the 1996 federal Telecommunications Act, which, among other provisions, requires the agency to report annually on the availability of advanced communications (i.e. broadband) for all Americans. If the report determines that service providers have failed to deploy service in a “reasonable and timely” fashion, the FCC must determine and take appropriate policy action. The 2019 report, which technically relies on data from the end of 2017, determines that over 21 million Americans lacked access to broadband at that time, but that the providers nevertheless deployed such service in both a reasonable and timely fashion due to the modest gains made over the previous year.

This fact alone is a major problem, but not nearly as problematic as the flawed methodology behind the reports themselves:

- The data are self-reported from the providers without adequate oversight. To be clear, there is nothing wrong with requiring providers to self-report. What is wrong is not double and triple-checking their work.

- Providers submit data for the report on advertised availability of broadband speeds. Advertised is very different from actual, and availability is very different from usage.

- The report relies solely on census block data. Depending on population density, census blocks can vary greatly in size just like state congressional delegations (consider Alaska’s one U.S. Congressional seat vs. California’s 52.) This means that if a provider reports the advertised availability of 25/3 mbps service anywhere in a census block, as far as the FCC is concerned, that entire block appears to be adequately served.

- Because the FCC only reports on advertised service availability, which points mostly to infrastructure, the agency tends to observe the digital divide through only that lens and omit consideration of price, education, and device ownership. This is not to diminish the need for critical broadband infrastructure. Due to the high cost, incentivizing the widespread deployment of capital construction is the most difficult public policy nut to crack. At the same time, policy makers and advocates must not lose sight of social and economic barriers that continue to impede digital adoption for many Americans.

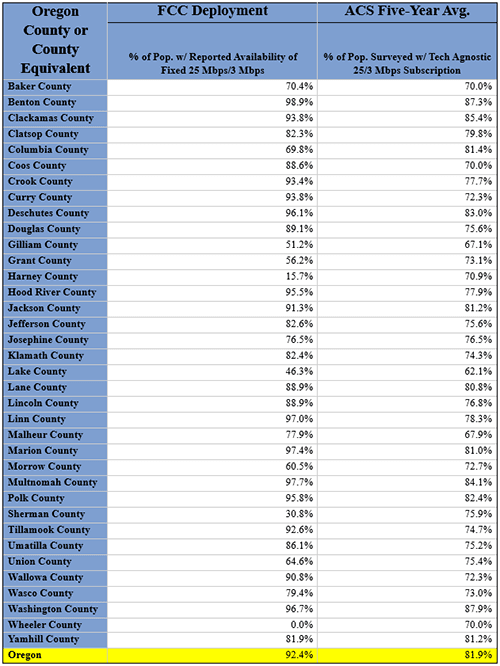

Now that I have explained the myriad issues with FCC broadband deployment reporting, it’s worth contrasting with what may be a more accurate view of digital adoption. Advocates have increasingly turned to ACS data to better understand the extent to which those other social barriers like cost, education, and device ownership impact digital adoption. Only when we overlay FCC deployment (advertised service availability data) with ACS adoption (usage) data do we get anywhere close to understanding the digital divide. Take Oregon for example:

The FCC reports that over 92 percent of Oregonians have “access” to fixed (wired to the home) broadband, whereas the ACS signals that only about 82 percent of residents use broadband service. This dynamic is similarly true in counties like Tillamook or Wallowa where nearly 93 and 91 percent of residents, respectively, enjoy access, but about 75 percent can take advantage of that purported access. The reverse is seen in counties that are largely rural: providers report that 15 percent of Harney County residents have access to broadband, but the usage report is much higher at 71 percent (this number includes wireless and satellite service but is still far too low for 2019).

Ultimately, these combined numbers indicate a stark digital divide in Oregon today, particularly among urban and rural communities.

However, there are two straightforward policy solutions to this vexing problem: leverage public money in the form of infrastructure and community planning grants, and centralize broadband policy analysis, development, and implementation. And it just so happens that two bills before the Oregon Legislature this session - HB 2184 and HB 2173 - aim to achieve both these aims while also stabilizing the existing Oregon Universal Service fund that pays for companies’ carrier of last resort obligations.

CUB prioritized these two bills at the start of the 2019 legislative session, and continues to advocate for their passage. But we still need your help and here are three ways you can do so:

- Sign onto our letter of support. We’ve collected signatures from Oregonians since February and will submit our letter before the final votes are cast in the House and Senate.

- Find your legislator and tell them you, as their constituent, are deeply concerned with the digital divide here in Oregon and, therefore, support both HB 2184 and HB 2173.

- Tell Senate President Peter Courtney and House Speaker Tina Kotek to prioritize these two bills in 2019 because any further delay to address the digital divide will harm Oregonians.

The 2019 Oregon legislative session is scheduled to end on June 30, so your attention to the above action steps is time sensitive. Look to CUB’s Summer Newsletter (become a CUB member to join our mailing list!) and future blog updates on these and other CUB legislative priorities.

To keep up with CUB, like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter!

09/05/22 | 0 Comments | FCC Broadband Deployment and Oregon Policy