Changing Oregon’s Regulatory Approach to Utilities’ EV Investments

Posted on March 20, 2019 by Bob Jenks

Tags, Energy

Oregon is a leading state in EV sales. In 2016 and 2018 it was the second leading state for percentage of vehicle sales that were EVs, and in 2017 it was third. Portland General Electric (PGE), for example, projects that there will be 100,000 EVs in its service territory in five years. However, CUB is concerned that the current regulatory approach limits Oregon’s ability to prepare to serve the growing load.

Under SB 1547, the Clean Electricity and Coal Transition Act which CUB helped pass into law in 2016, Oregon utilities are required to produce transportation electrification plans with a goal of accelerating transportation electrification. But the regulatory approach that Oregon takes in evaluating utility investments will never find such investments to be cost effective. This has limited utilities to proposing pilot programs that are not cost effective on their face, but are justified based on the “learning” from the pilot.

There are two variables at play in this issue:

Focus on Accelerating Electrification

As stated in the text of SB 1547:

The Public Utility Commission [PUC] shall direct each electric company to file applications, in a form and manner prescribed by the commission, for programs to accelerate transportation electrification. A program proposed by an electric company may include prudent investments in or customer rebates for electric vehicle charging and related infrastructure.

Requirement that Investments Be Cost Effective

This requirement appeared several years ago when the PUC first developed rules around EVs. The PUC’s initial EV program was discretionary, so they required a net benefit. The passage of SB 1547 introduced a requirement that utility expenditures be prudent. The PUC rules related to SB 1547 defined prudency based on net benefit. Utility transportation electrification plans are required to show how a “net benefit to ratepayers is attainable”.

It is the combining of these two approaches that problematically limits investment for expected EV load.

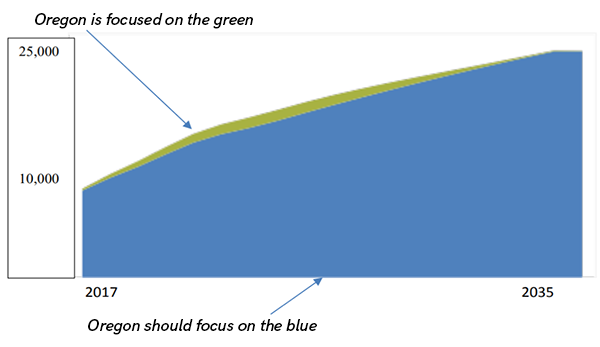

The focus on accelerating transportation has led to programs being judged based on how many new EVs purchases they will generate. The above graph shows the expected growth in EV sales in PGE’s service territory, from 2017 through 2035. The blue area represents the baseline volume of EVs that will exist in the entire service territory if the utility does nothing, while the green area represents the acceleration of EV adoptions caused by utility programs. If the utility has a program that provides public charging stations (either directly by the utility, or through grants) those charging stations will be used by both baseline EVs and the EVs attributable to the utility investment. While that charging investment will serve EV users generally, the baseline of EVs that would have existed without the utility investment are considered “free riders” and are removed from the evaluation of the investment’s net benefits.

The result is that it is nearly impossible for a utility to make a cost-effective investment that facilitates EV charging. The bulk of the EV load is made up of free riders, so the utility investment must be justified based on a small subset of EV users.

Additionally, this approach requires a determination of attribution. How many of the new EVs are on the system specifically because of the utility’s EV programs? This is not an easy question to answer. Consider a utility that forecasts a baseline of 100,000 EVs and thinks its program can increase that by 10 percent, or 10,000 vehicles. In the real world we end up with 105,000 vehicles. Did the utility program only add 5,000 vehicles, or did we get the baseline wrong?

This is not how we typically treat utility investments that are designed to serve new load. EVs represent new load added to the system. But the regulatory system treats them differently than other new load sources, such as newly built residential dwellings or office parks.

Utilities are generally allowed to spend money to serve new load based on the premise that if the additional cost of adding a new customer is below the contribution that new customer will make toward joint and common costs, the new customer is cost effective.

In the case of PGE, this allowance is $1623 per new residential dwelling. Because this is mostly capital investment that is spread over the life of the equipment, in the first year the cost to the utility system is about ¼ of the contribution the new customer will make to the joint and common costs. Therefore, the investment is considered cost-effective.

Without considering the contribution that EVs make to the system’s joint and common costs, utility spending on EVs is generally not cost effective. However, there is one exception to utility cost effectiveness: pilot programs where the utility gains valuable knowledge and experience. Therefore EV programs are established as pilot programs and justified because of the knowledge the utility gains. But with 100,000 new EVs coming in the next five years and more being added to the system later, the focus should be on how EVs impact the utility system, and how utilities should best be serving EV load.

Moving Beyond Pilots

Oregon needs to change its regulatory approach to EVs. Rather than focus on the acceleration of EVs caused by utility programs, we should focus on the impact that more than 100,000 EVs will have on the utility system. The new load of EVs will help pay for joint and common costs, and this benefit should be recognized. At the same time, new investments will have to be made to accommodate this load. Just as with new homes and commercial buildings, the amount that utilities are allowed to spend on meeting new EV load should be based on an analysis of the new load’s costs and benefits.

To keep up with CUB, like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter!

03/20/19 | 0 Comments | Changing Oregon’s Regulatory Approach to Utilities’ EV Investments